The Electron Paradox: Why The Best Desktop Apps Are Just Websites in Disguise

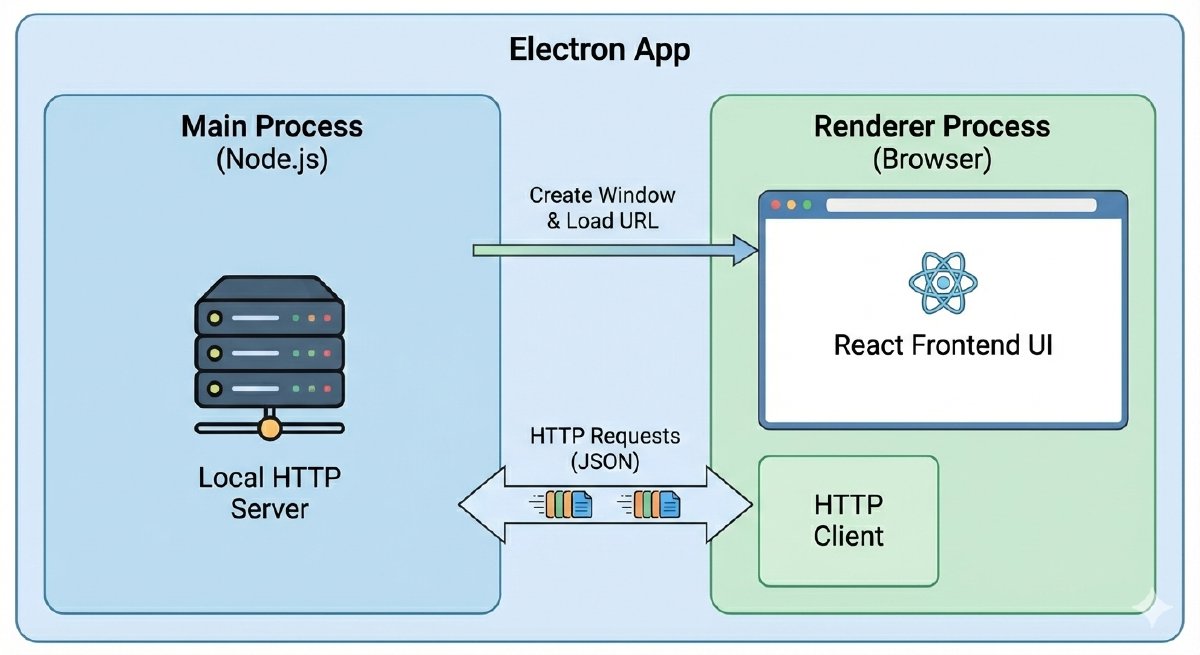

I’m building an AI desktop assistant, and the architecture would make any computer science professor weep: a React frontend making HTTP requests to an Express server running in the same application. Data gets serialized to JSON twice—once outbound, once inbound—just to shuffle it between memory locations on the same machine. It’s absurd.

As an engineer, I hate Electron: memory bloat (150–300MB+ per instance), slow startups, huge bundles (100MB+ for simple apps), quirky IPC debugging, uncanny valley UX that ignores OS conventions, security risks from bundled Chromium, clunky tooling, and pointless legacy baggage like the macOS Xbox 360 controller driver (a dormant Chromium relic for gamepad support that no productivity app needs).

But as a businessman building real products, I love it: one codebase, one team, instant hot reload, massive npm ecosystem, easy hiring of React developers, and shipping features months faster than fighting native fragmentation across three platforms.

This architecture ships products. The alternatives rarely do.

The Electron Honor Roll: You’re In Good Company

Microsoft’s VS Code remains the world’s most popular code editor, despite Microsoft owning Windows and decades of native framework experience. They chose Electron for VS Code (2015) and Teams (2017). Discord now serves over 200 million monthly active users with real-time voice, video, and text—far from simple CRUD. Slack powers enterprise communication at Fortune 500 scale. These companies have vast resources and engineering talent. If pure native were viable for cross-platform reach, they’d pursue it. The pattern is unmistakable: in 2026, serious cross-platform desktop software means Electron.

The Great Divergence: How Web Ate Desktop’s Lunch

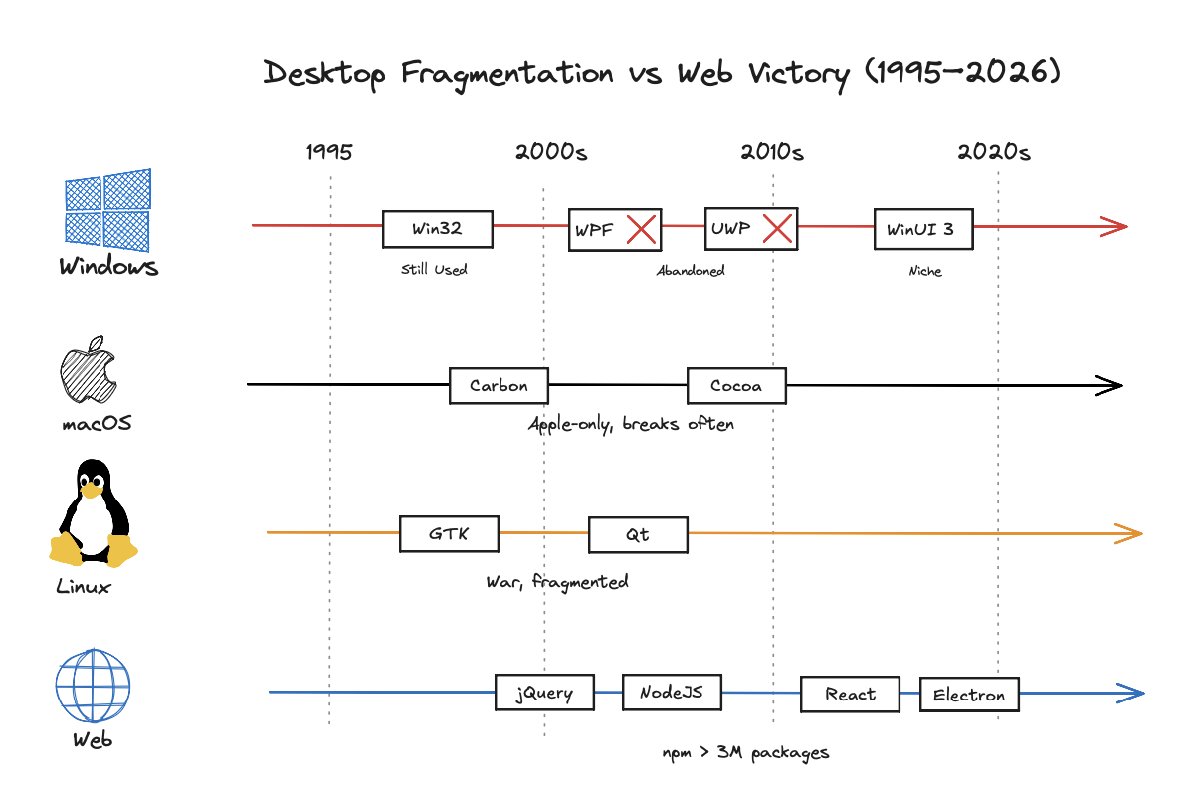

In the 1990s, desktop ruled. Developers targeted Win32 (Windows), Cocoa (macOS), or GTK/Qt (Linux). The web was for static documents. Gmail (2004) and Google Maps (2005) showed web apps could feel dynamic. jQuery tamed the DOM. Then Node.js (2009) brought JavaScript to the server, enabling full-stack JS. The npm ecosystem exploded: hundreds of thousands of packages by 2015, over 1.3 million by 2020, and exceeding 3 million by 2026. React (2013) popularized component-based UIs, followed by Angular and Vue. Hot module replacement (HMR) transformed development: change code, see updates instantly in the browser. Native rebuild cycles? Minutes of compile-test-restart.

Meanwhile, desktop platforms stagnated amid fragmentation. Microsoft cycled through Win32 (still dominant), WPF (2006), UWP (2015), and WinUI 3 (2021)—each promised as “the future” before fading. Linux split between GTK and Qt with ongoing desktop environment divides. macOS offered stability but remained Apple-only, with Swift/Objective-C learning curves and periodic compatibility breaks. Mobile added iOS (2007) and Android (2008), forcing expertise across five platforms with incompatible languages and tools.

The Fragmentation Tax

True native cross-platform development in 2026 demands:

- Multiple codebases (C++/C# for Windows, Swift/Obj-C for macOS, C/C++ for Linux)

- Separate build systems (Visual Studio, Xcode, CMake)

- Platform-specific QA and update mechanisms

- Hiring specialists versed in rare combinations of Win32, Cocoa, and GTK

Result: prohibitive costs, slower velocity, or abandoned platforms. Most teams target one OS or deliver mediocre ports. Cross-platform native desktop is effectively dead.

Have you ever ported a complex app to three platforms? The hidden taxes in bugs, testing, and maintenance quickly become overwhelming.

Why Web Won: Economics, Not Technology

Cross-platform by default: one codebase deploys everywhere with shared fixes, features, and tests. No vendor lock-in—HTML/CSS/JS standards evolve via W3C and WHATWG. Learn React once; it runs identically across all operating systems.

The npm explosion provides unmatched libraries: OAuth, charts, state management—all a quick npm install away. NuGet (~463,000 packages) and CocoaPods (~100,000, soon read-only) can’t compete. Developer experience shines with millisecond HMR, Chrome DevTools, abundant tutorials, and rapid language evolution (ES6+, TypeScript, hooks in React). Native cycles remain slow; documentation fragmented.

Microsoft’s Verdict: Owning Windows and creating WPF, UWP, and WinUI didn’t stop them choosing Electron. The economics—avoiding 3x costs, teams, and delays—won out. When the platform owner abandons native for cross-platform web tech, the platform is officially dead.

The Cost of Convenience: Why the Overhead Is Worth It

Electron’s drawbacks are real: 150-300MB+ memory, IPC/JSON serialization latency, slower startups, battery drain, and imperfect native fidelity. Computer science purists rightly critique it.

But is the alternative any better? Triple the development cost, smaller ecosystems, hiring struggles, slower iteration, and delayed (or abandoned) features. Users prioritize working features over architectural purity. Shipping months faster with Electron beats perfection that never arrives.

AI Tooling and the New Generation of Development

You can argue that with AI coding assistants (Copilot, Cursor, Claude, etc.) you can write code once—say in JS/React—and auto-duplicate it for native platforms (Swift, C++/C#, etc.). Prototyping speeds up, boilerplate appears instantly. But does this kill the need for three codebases? No. AI-generated ports are often messy: hallucinations cause logic bugs, platform quirks (macOS sandboxing, Windows scaling, Linux theming) get ignored, security holes slip in, and architectural debt builds fast. You still maintain three separate codebases—endless human fixes, debugging, and refactoring follow.

How much do you trust AI with C++ memory management, SwiftUI state, or concurrency races without constant supervision? Rarely. Native toolchains lag in AI quality compared to JavaScript/React, widening—not closing—the gap.

Result: AI amplifies Electron/web advantages (uniform ecosystem, better suggestions, single codebase) far more than it rescues native multi-platform development. Pragmatic velocity still favors one codebase over AI-assisted triple maintenance.

The Future: Alternatives Aren’t Catching Up

Tauri (Rust + OS webview) offers smaller bundles (10-50MB) and lower overhead, using Safari WebKit on macOS or Edge on Windows. With ~102k GitHub stars (vs. Electron’s ~120k after a seven-year head start), its ecosystem remains smaller; adoption grows but hasn’t displaced Electron in major apps.

Flutter Desktop delivers strong performance but faces Dart adoption barriers and desktop immaturity (stable 2022).

.NET MAUI targets cross-platform C# but inherits Microsoft’s mixed track record and Windows bias.

All alternatives either rely on web rendering (Tauri) or struggle with ecosystem maturity and developer mindshare. Will any displace Electron soon, or has the head start proven insurmountable?

The Equilibrium

Desktop platforms treat APIs as moats; cooperation seems unlikely. Electron effectively becomes the de facto standard. The inefficiency isn’t a flaw—it’s the rational equilibrium in a fragmented world. Progressive Web Apps (PWAs) may further blur lines, making the browser the universal runtime.

Embracing the Paradox

My AI assistant runs this “absurd” stack: double JSON serialization, localhost server in a desktop wrapper, full browser runtime bundled. Despite my frustrations with its inefficiencies and tooling, it’s the right pragmatic decision. Separate native codebases in Swift, C++, and Qt? Delaying features by months for triple implementation? No thanks.

When VS Code, Discord, Slack, Teams, Figma, Notion, and others choose Electron, it’s no coincidence. Smart teams make economic bets on velocity and reach. The “right” architecture ships products, hires easily, and leverages 3+ million packages—not the most elegant on paper.

In 2026, building cross-platform desktop means writing a website in disguise. That’s not compromise—it’s the pragmatic response to decades of platform failure.